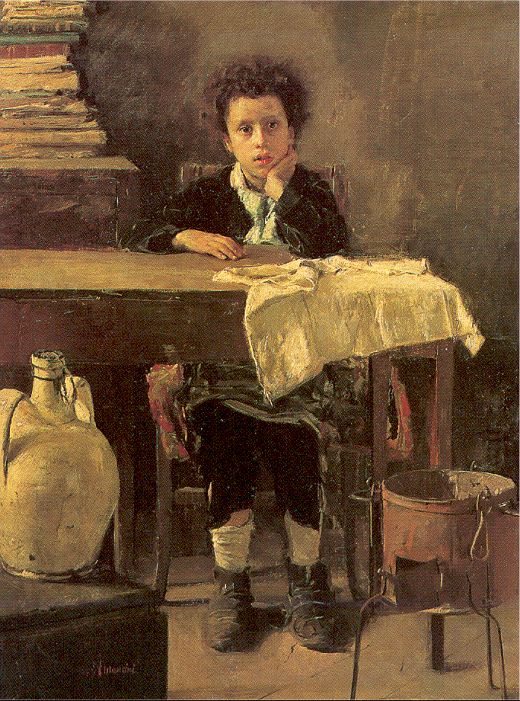

Children as labor force: Shattered memories from a lost childhood

Children as labor force:

Shattered memories from a lost childhood

We work to live.

Mainly, because we have to: work provides us the money with which we can buy food, clothes and other materialistic needs.

Secondly, because it allows us to enjoy what we want, including some leisure time between one demanding task and another.

Thirdly, because no matter how we look at it, work is what we need to do, in order to stay alive.

However, in time, work has become more than just a means to live. It has turned into a purpose. The burden is now a career.

Maybe it’s the modern spirit, an era that centers on the individual, achieving more than he can take.

Maybe it’s the work itself, no longer a necessity but a personal, fulfilling expression.

One way or the other, the change has happened and it continues to strike roots.

Adults can choose the way in which they articulate themselves:

They have the possibility of resigning from a job that doesn’t suit their qualifications. They can compromise until they get a job they want.

They can hate their job, and groan loudly until they receive their paycheck at the end of the month.

Nine times out of ten, the choice is theirs.

But what about children?

Children who don’t need to work but do so anyhow?

Children in unbearable circumstances, where concepts such as personal expression just don’t apply?

Children like Varka in Sleepy1 and Vanka in Vanka2 by Anton Chekhov, to whom there is no real opportunity for another life. A life in which they won’t have to work and could just live, the way children do.

Varka, a thirteen year old girl, labors all day with endless housework at the shoemaker’s home and workshop, where she works and lives. Her story begins with a description of her nightly events. People usually sleep at night, resting from their daily chores, but not Varka. Even at night she is compelled to work, rocking the cradle of the shoemaker’s forever-screaming infant. Even without a voice he continues to shriek and Varka is exhausted. The world around her becomes foggy and blurred. As opposed to daytime, when she’s constantly required to toil and run incessantly from one place to another, at night she’s bound to stand guard and watch the baby. The chance to rest, as she stays in one place, task-free, is cruelly denied of her. Varka can’t sleep. She has no permission to sleep. She must rock the cradle and sing to the baby until he calms down. But he never does.

Varka herself is just a girl. She can’t sustain such ruthless chores. And thus, unwillingly, she dozes a little, not sleeping but hallucinating bits of memories from her childhood.

“She sees herself in a dark stuffy hut. Her dead father, Yefim Stepanov, is tossing from side to side on the floor. She does not see him, but she hears him moaning and rolling on the floor from pain. “His guts have burst,” as he says; the pain is so violent that he cannot utter a single word, and can only draw in his breath and clack his teeth like the rattling of a drum… Her mother, Pelageya, has run to the master’s house to say that Yefim is dying. She has been gone a long time, and ought to be back. Varka lies awake on the stove, and hears her father’s “boo–boo–boo.” And then she hears someone has driven up to the hut. It is a young doctor from the town, who has been sent from the big house where he is staying on a visit. The doctor comes into the hut.”3

But the doctor can’t save Yefim Stepanov. He must bring him to a hospital, where they will operate on him immediately. The doctor goes, the master sends a cart, Yefim prepares himself and drives off. But it was all too late: “Varka goes out into the road and cries there, but all at once someone hits her on the back of her head so hard that her forehead knocks against a birch tree. She raises her eyes, and sees facing her, her master, the shoemaker.”What are you about, you scabby slut?” he says. “The child is crying, and you are asleep!” “4

After Yefim’s death, Varka and her mother go to the city, to find work. This horrible chain of events has lead Varka to her very realistic hell, as a servant – slave in the cobbler’s house. The cobbler himself is not a rich man. He too suffers from a lack of worldly goods deficiency, and is not familiar with the taste of steady wealth and richness. He is a vulgar, crude and a common human being. He and his wife are troubled with the burden of everyday life, heavy weight that takes away their time, sensitivity and compassion. These important aspects are most needed in order to formulate a decent society. However, if ideology is, sometimes, a matter reserved to those with financial means and leisure time, so can morality be a matter of geography: to a man occupied with daily minutiae there is neither time nor patience to deal with feelings, considerations and understanding. If a person suffers distress right before his eyes, he might not even see it. Or, he can see but he wouldn’t even care.

He has to survive first. Then he can handle everything else.

But who has time to handle everything else, when surviving is so difficult and takes up so much time?

At the story’s second night, guests come to the shoemaker and his wife5. Again, Varka has to work incessantly: five times she heats the samovar, runs to buy wine and three bottles of beer, fetched vodka and the corkscrew, cleans a herring, runs to the shed for firewood, splits it into pieces, heats the first stove, oils her master’s galoshes, washes the steps, sweeps and dusts the rooms, heats the second stove, peels potatoes, washes, sews and attends the customers. She does it all, without a single pause, without a moment of rest and without sleep. Not even at night, because then, just like every other night, the crying baby shrieks for her attention.

The story ends in a heartbreaking tone.

Varka kills the crying baby, the cobbler’s son6.

Looking into the facts, she strangles him to death.

Looking into Varka’s mind, she’s stupid from exhaustion that she loses her sanity.

But sanity is not an acceptable term in Varka’s world.

In Varka’s world there is no room to understand the anguish and frustration of the torment “I”.

There is only what you did, and what you didn’t do.

If someone talked to Varka about fulfillment, personal accomplishment, a career – she would not understand what that someone was saying. Varka’s can’t simply add an additional supplementary need to the basic desire to survive. Therefore she works, constantly, without any complaint. This is her way to live another day.

The crying baby also struggles to survive. He screams out the fact the something troubles him and makes it impossible for him to live, the same way he inflicts pain to poor Varka.

Two lost creatures in a doomed world, a world of indifference and detachment.

Two children, just trying to sleep.

Trying, but failing miserably.

Young Vanka, to his much regret, suffers the same miserable misfortune.

Vanka, only nine years old, also toils at a shoemaker’s workshop, like Varka. There he lives and works, since his parents died. The story takes place at Christmas Eve, while Vanka is waiting for his employer, his wife and apprentices to leave to church. After they had vanished, Vanka “took out of his master’s cupboard a bottle of ink and a pen with a rusty nib, and, spreading out a crumpled sheet of paper in front of him, began writing. Before forming the first letter he several times looked round fearfully at the door and the windows, stole a glance at the dark ikon… and heaved a broken sigh.”7

Vanka writes to his dear grandfather8, Konstantin Makaritch, implores him to bring him back home9. He tells him about the ordeals, about the teasing, the whipping and the insults. He remembers his grandfather’s ever smiling vital character: “old man of sixty-five, with an everlasting laughing face and drunken eyes. By day he slept in the servants’ kitchen, or made jokes with the cooks; at night, wrapped in an ample sheepskin, he walked round the grounds and tapped with his little mallet”10. This is not a respectable and impressive grandfather. This is a grandfather who is a savage rascal, an immature child. But Vanka wants to go back to him, to go back home, to the village that appears to him as out of a fairy tale “with its white roofs and coils of smoke coming from the chimneys, the trees silvered with hoar frost, the snowdrifts. The whole sky spangled with gay twinkling stars, and the Milky Way is as distinct as though it had been washed and rubbed with snow for a holiday…”11

Christmas is a family holiday for Christians. But Vanka, only nine years old, is all alone. There, at this grandfather’s house – everything is merry, full of life and warmth. Here, at the cobbler’s workshop, everything is gray, scary, alienated and dreadful.

Vanka’s memories, very much like Varka’s, unfold as the story progresses, stretch out to his mother and Olga Ignatyevna who gave him goodies and taught him to read and write. She had done all those things because she had nothing better to do. Things Vanka’s practical, realistic world doesn’t require.

Vanka and Varka are not really interested in education. It will not help them run and fetch whatever they are told to bring, draw water and sweep the floors, feed and wash, polish and shine. Therefore, why bother with education?

Vanka does not understand that he unloads his difficult, sore feelings onto the paper.

Psychologists would probably explain that he was processing his bitter thoughts and confronting the tragedy of his condition.

But Vanka is not aware of all of this.

Vanka only writes to his grandfather, pleading that he should come to take him home.

To those who seek the bread and can’t even imagine the possibility of butter, the world is very simple, a linear place: one works to keep on living. There is no other choice.

Vanka and Varka want to finish their work so they can return to life, not fulfill it.

Vanka wants to go home.

Varka wants to sleep.

But Vanka, like Varka, fails. In his naivety and ignorance, he puts the letter into an envelope and then scribbles – “To grandfather in the village. Then he scratched his head, thought a little, and added: Konstantin Makaritch”.

It’s pointless to say that the reader understands that Varka hoped in vain: the letter will never reach his grandfather.

The narrator himself insinuates that this will be the case, at the opening exposition: “Vanka Zhukov, a boy of nine, who had been for three months apprenticed to Alyahin the shoemaker, was sitting up on Christmas Eve. Waiting till his master and mistress and their workmen had gone to the midnight service, he took out of his master’s cupboard a bottle of ink and a pen with a rusty nib, and, spreading out a crumpled sheet of paper in front of him, began writing. Before forming the first letter he several times looked round fearfully at the door and the windows, stole a glance at the dark icon, on both sides of which stretched shelves full of lasts, and heaved a broken sigh. The paper lay on the bench while he knelt before it”12

Vanka kneels as Christians kneel before the icon. But Vanka doesn’t pray to the icon. He prays for his letter. It is the object of his wishes and hopes. But the paper is wrinkled, the pen is rusty and the bottle of ink is too tiny, it’s doesn’t suffice for Vana’s writing.

It does not hold enough ink for Vanka to write.

Vanka’s savior can’t redeem him.

But who will explain that to him?

Who will explain to him that his letter will never arrive at its destination?

Who will explain to him that the injustice he is suffering was never supposed to happen in the first place?

Who will explain to him that a nine year old boy should go to school, to learn how to read and write, not only because there isn’t anything else better to do?

No one.

Not in Vanka’s times.

But for whom does Chekhov write his stories, if not for people in Vanka’s times?

Can only the modern generation understand his words? Be shaken at the unfairness and stupidity?

Doesn’t the person who write those things, already understand them himself?

In modern times there is an idealization about work. It has turned into a means of self-expression. But this idealization doesn’t apply to children. Children are children. Young people in an abstract disposition who only feel hungry – tired – bored.

Children don’t want to build a personality or a character. They don’t even know such things exist, or that they matter. Their reality is what happens here and now or what was and is now no longer.

Varka and Vanka lived in an era when effort was as common as breathing. Work was not an aspect one can criticize and condemn. The difficulty was natural and necessary, without boundaries, without pause, endless and permanent. It was a way of life.

Varka and Vanka share many similarities: their names13, the chores they are required to do, their shoemaker manager, their mothers names14, the fact that they are both orphans, the way that the furniture throws daunting shadows over the walls, the crying infant they need to rock until he sleeps, the beatings they get.

Only one thing tells them apart:

Vanka weeps and wants to go home. His world is a collection of plain, mundane experiences15. His memories belong to a beautiful world, so naïve and so lost.

When Varka hallucinates on her past, she dreams of shadows, clouds, people, carts, thick forests and back ravens. In her delusional dreams there is no peace, no comfort, no anchor.

Varka has no good experiences to cling to.

In her childhood there are no fine memories.

There is no hope.

Varka, unlike Vanka, doesn’t daydream anymore.

Life has already taught her that lesson.

Vanka fumes because he is only a boy, who has the inexperienced insight of someone who didn’t quite adjust to the world as it is.

Varka fumes no more.

A small, lost child, trapped in the madness of workaholic world.

A world that does not understand the meaning of “personal fulfillment”.

A world without a choice.

Could Varka understand our modern workaholic existence?

Could we understand it better thanks to her?